Break a stick in two random points, can you then build a triangle?

Here is an interesting problem that involves probability. Can you guess the answer?

Consider a stick of length 1. Select two points uniformly at random on the stick and break the stick at those points. What is the probability that the three segments form a triangle?

Where does this problem come from?

After a short research, this problem appeared in one of the Senate-House Examinations (or later known as Mathematical Tripos) back in 1850 in Cambridge. From that point on, it became one of the many classical problems in continuous random variables. For instance, Poincaré included this problem in his Calcul des Probabilités (1986). Although not so recent, this paper by Dr. Goodman brings a great review on the multiple solutions and the history behind this problem. What makes this problem interesting to me is not the actual value of the probability of forming a triangle, but how the to get there.

The first challenge is to acknowledge that is is not always possible to make a triangle out of 3 segments. Asking friends, I’ve got the answers 1, 1/2 and 0 (in order of frequency). One of the reasons why I am writing this blog entry is because both of these solutions are very different from the canonical solution I find over the web.

I came across this problem during the 3rd QCBio Retreat, during the lunch break. I immediatelly started to give a shot solving it, but got stuck. While I was doing that, another guy in our table came up with a quite interesting solution. In the afternoon I was able to close my calculations.

Let me thank Brenno Barbosa for helping me cut a step in my formal solution.

And since we’re talking about triangles…

Why is it not always possible to form a triangle?

The first challenge is to recognize that you can’t always build a triangle with the three resulting segments regardless of where you break the sick.

A simple counterexample is when you break the stick in two very close to one of the ends. As a result, two of the segments are too short, and the third one is very long. In this case, you can’t connect all three vertices.

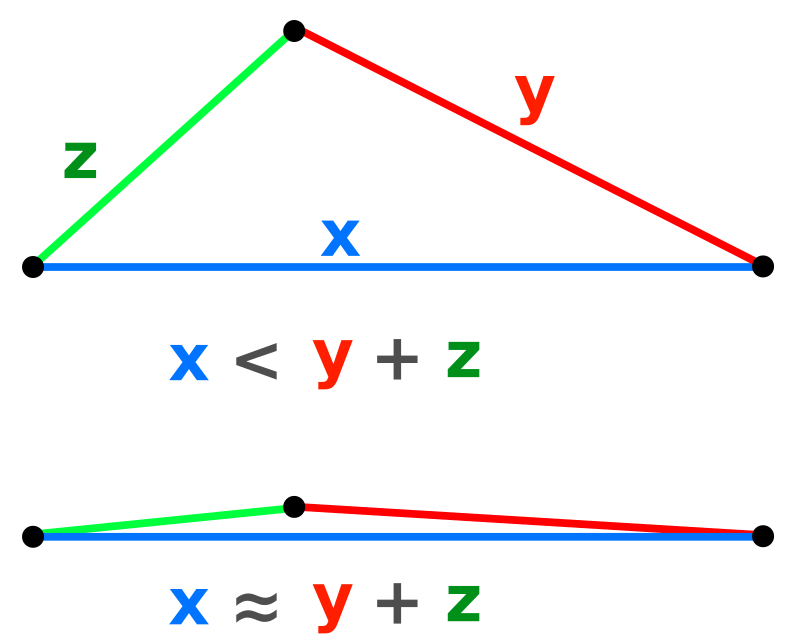

The actual constraint to form a triangle is the triangle inequality. Let $x$, $y$, and $z$ be length of each of the three vertices of the triangle. Then, the triangle inequality can be written as

Here is a way to visualize this inequality:

To connect this with the problem at hand, assume that $ x + y + z = 1 $ and that the two randomly chosen points were $x$ and $x+y$. However, in this case, we also must satisfy

and

Any solution $(x,y,z)$ that does not satisfy all of the equations above represents a possibility of breaking the stick and not being able to build a triangle with the resulting three segments.

A clever and direct solution: graphically enumerating the solutions

Let’s assume points $A$ and $B$ are the two points selected. The three inequalities from the previous section define a region of the plane $A$ and $B$ in which solutions are admissible. If we can somehow calculate the area of that region and normalize it, that solves the problem.

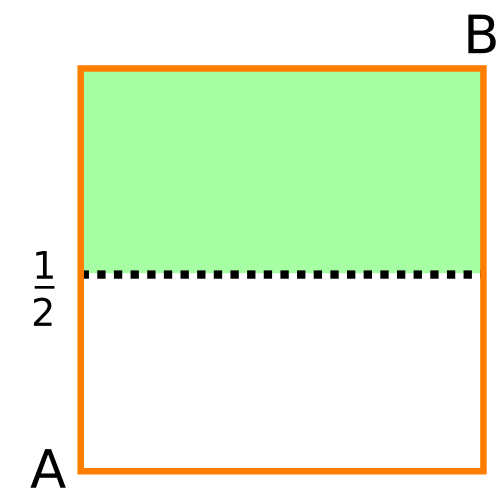

Here is how. Assume $A < B$, i.e., $A = x$ and $B = y + x$. From the first inequality, $A < 1/2$ must be satisfied. If $A$ is larger than half of the stick, then no point $B$ satisfies the triangle inequality.

Let’s draw the $A \times B$ plane: on the x-axis, all possible values of $A$; and the y-axis, all values of $B$. So, only the green shaded area is valid:

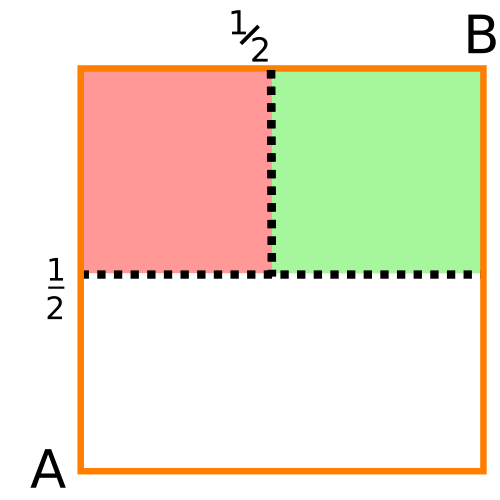

Because of the last inequality, if $B$ is also lower than $1/2$, then the third segment ($z$) is larger than the sum of the first two segments. This fact restricts the region of admissible regions further (on the green area):

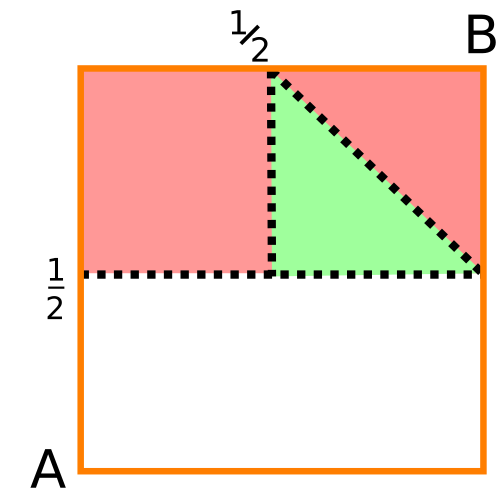

The last condition is that the middle segment, between points $A$ and $B$, is not larger than the other two. To ensure that, $B < A + \tfrac{1}{2}$. This last inequality defined a straight line in the $A \times B$ plane:

Thus, the area is $1/4$ of the the admissible area, which is the probability of forming a triangle with the resulting broken segments.

I think this is a pretty creative and powerful solution, and to me . The only problem is when the problem gets harder, it becomes harder to come up with solutions like this one. So, next we will address this same problem but using elementary probability theory to come up with a purely anaytical solution.

Quick Python script to numerically test the answer

Why not estimate this probability using a simple simulation? We can do that with a few simple lines of code. Here is an example.

With 10000 samples, the result is:

$ python testing_triangle.py

P(triangle) = 0.2505

Relative error = 0.0020

A formal solution using elementary probability

Again, the graphical solution above is clever, and fast – you can explain it in less than 5 minutes. However, this problem is a great exercise of elementary probability, and by solving it with a more formal approach we will be able to apply the same reasoning to solve other interesting problems (more on this below).

First, assume that we selected points A and B at random with a unfirom distribution, i.e.,

Of course, this assumes $A$ and $B$ independent (or $ A \perp B $), which is always implicitly assumed. A priori, we don’t know which of the points $A$ or $B$ are closer to one end or the other. So, let’s define two new variables:

and

Although this may seem harder, this is the reason why I got stuck in the first place (so, thanks Brenno for the tip!). It will be easier this way.

All thee inequalities that we wrote based on the triangle inequalities can then be re-written in the following form:

Therefore, it is easy to define the event “form a triangle”, denoted by the symbol $\bigtriangleup$:

Fine, so the probability we want to calculate is

where $dF$ is the joint probability density of $X$ and $Y$. There is an easy way to evaluate it: First, for $x < y$, we have

Naturally, for $ x \geq y $, $ F\left( [ X \leq x , Y > y ] \right) = 0 $ by definition.

Note that we chose to measure events $[X \leq x]$ and $[Y > y]$ because they are disjoint and, thus, independent. Also, because we assumed $ A \perp B $ and using the fact that the uniform distribution $F(X\leq x) = x$, then

Therefore, the join distribution of $X$ and $Y$ is

The joint probability density is (let me try and make it very explicit)

Finally, going back to the original probability:

by Fubini’s theorem.

Thus, $ \mathbb{P} \left( \bigtriangleup \right) = 1 / 4 $ is our final answer. Note that, at the end of the day, the domain of integration of the integral we just solved is exactly the same as the region defined in the graphic solution above.

Why bother with probability if there is a faster solution…?

This is always a great question: why do we bother (and why should you) with a more formal solution to this problem, if the one above does the job?

Problems like the Broken Stick can be extended very easily. Dr. Hildebrand, for instance, has wrote these interesting notes - probably for his calculus class - where he discusses this problem and proposes other possible related problems. In some cases, he studies the solution numerically.